What People Don’t Tell You About Product Management..!!!

By Jason Shen

I’ve flipped from founder (Ridejoy) to product manager (Etsy) to founder again (I’m one week into something new). Being good at one is not the same as being good at the other.

Product Management is a great job if you like being involved in all aspects of a product — but it’s not a great job if you want to feel like a CEO.

Below are what research and my own in-the-trenches experience taught me about excelling as a Product Manager.

Why Product Management Was Invented and Why This Job Matters

The role of product manager stems back to the 1930s, when an executive at Procter and Gamble created a new role he wanted to hire for, one that would try to channel the needs of the customer, and follow a product from conception, through development, to launch, and beyond. The goal was to have a cross-functional leader coordinating between R&D, Sales, Marketing, Manufacturing, and Operations.

That Procter executive, Neil McElroy, took the product manager idea to NASA and later Stanford, where he advised two young entrepreneurs, Bill Hewlett and David Packard, which led HP to adopt the product manager role as well.

On a parallel track, up in Washington, Microsoft also played an important role in the conception of the modern product manager role. What Microsoft found in the 1980s building Excel for the Mac was that the project was a significant technical challenge. That challenge: building a spreadsheet tool that leveraged new GUI elements on an operating system they weren’t familiar with and didn’t control.

That challenge led the engineering team into the weeds. It was all they could handle to get the details right, and that pulled their attention away from bigger-picture issues.

Here’s how former PM Scott Berkun describes one of the first product managers at Microsoft.

A wise man named Jabe Blumenthal realized that there could be a special job where an individual would be involved with these two functions, playing a role of both leadership and coordination. He’d be involved in the project from day one of planning, all the way through the last day of testing. It had to be someone who was at least technical enough to work with and earn the respect of programmers, but also someone who had talents and interests for broader participation in how products were made.

The role McElroy created at P&G has morphed into something known as a “brand manager” within the consumer goods industry, someone who leads and coordinates pricing, promotion, placement, and occasionally the features of a product or set of products.

And within tech, McElroy’s invention is the product manager role that is now an important and hotly-desired job in tech.

The Rapid Growth of Product Manager as a Job

Last year, the Wall Street Journal published a piece with this lede: “So much for buyout titans. The current crop of M.B.A. students has a new dream job: Product manager.” According to WSJ, 6 to 7 percent of the most recent class of Harvard Business School grads took jobs in product management, with a product management 101 course at HBS getting 2 to 3 times more applicants than available seats.

This trend has been building for some time.

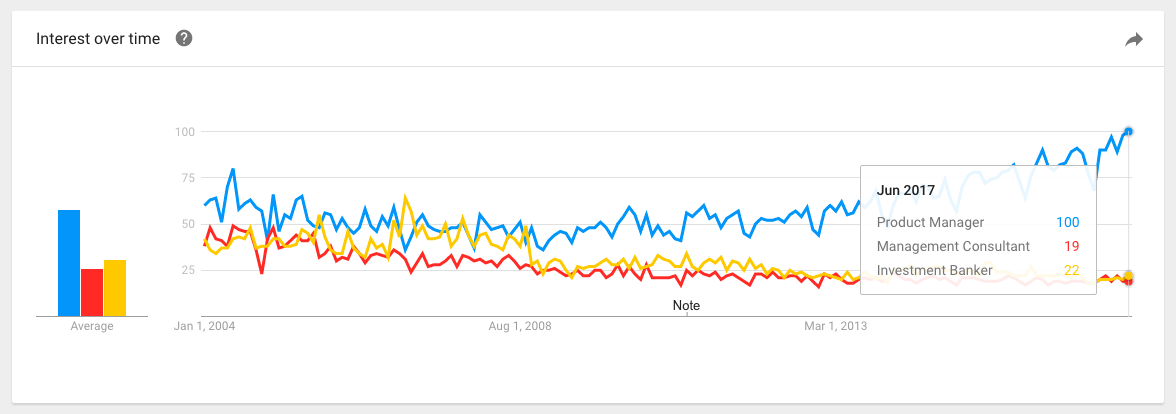

In the past 5 years, interest in the term Product Manager have doubled in the United States, and has dramatically outpaced interest in Management Consultant and Investment Banker, which had their heyday in an earlier period. The interest is most concentrated in states with major tech hubs like California, Massachusetts, Washington, and to a lesser degree, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois.

As people enter this field, there are certain myths that many believe about product management that are mistaken, and need to be cleared up.

The Desire to Play CEO

There’s a long-standing and insidious myth that product managers act like CEOs of the product or feature.

Where does this come from? The earliest example I could find is Ben Horowitz’s “Good Product Manager, Bad Product Manager,” which he wrote as VP of Product at Netscape in 1998.

A good product manager is the CEO of the product. A good product manager takes full responsibility and measures themselves in terms of the success of the product. The are responsible for right product/right time and all that entails.

When Ben posted this on the Andreessen Horowitz blog in 2012, he caveated it by saying this: “Warning: This document was written 15 years ago and is probably not relevant for today’s product managers. I present it here merely as an example of a useful training document.” (emphasis added).

Despite this disclaimer, the idea that being a product manager and being a CEO are similar has stuck.

The management consulting firm, McKinsey parrots this language in “Product managers for the digital world”, the most popular article in their High Tech section:

The product manager of today is increasingly the mini-CEO of the product. They wear many hats, using a broad knowledge base to make trade-off decisions, and bring together cross-functional teams, ensuring alignment between diverse functions. What’s more, product management is emerging as the new training ground for future tech CEOs.

This is of course what so many recently minted MBAs and ambitious people everywhere want to hear. It is Mr. McGuire whispering in their ears, “Two words: Product Management”.

But the truth is, being a CEO and being a product manager differ in important ways:

- CEOs set company strategy. Product managers are mostly trying to make sure their teams are working in line with the strategy set higher up the organization, or if they are working on strategy, are just one voice trying to influence a much bigger conversation.

- CEOs have the ability to hire and fire. Most product managers usually do not, unless they manage other PMs and then it’s only their direct reports, not the folks in design or engineering.

- CEOs have the ability to set budget and allocate resources. Most product managers do not, again, unless they are very far up the management chain, and even then, it’s often staffing PMs for projects, rather than hiring a whole additional engineering team to pursue a new line of work.

- CEOs mostly focus on the big picture. That’s not to say they get in the weeds, on their finances, on a senior hire, on a big product launch, but product managers have a responsibility to sweat a lot of details.

The end of the WSJ article says it best:

“Words like ‘vision’ and ‘CEO of the product’ get thrown around” by some students, but the job comprises administrative duties, too, said Prem Ramaswami, a senior product manager at Google Inc. who graduated from Harvard Business School in 2013 and worked with Mr. Eisenmann to launch the product course.

With note-taking and scheduling responsibilities, he said, “it’s more like being the glorified admin.”

That might not sound appealing — but understanding the reality of the PM role is much less frustrating than going into this career thinking you get to be the boss of every project.

Setting Strategy vs Making Strategy Happen

One of the key tasks of a CEO is to set the strategy of the company. Defining the mission of the organization, the key outcomes it needs to achieve in the next 3–6 years, and the approach it needs to take to reach those outcomes.

You can argue about whether or not CEOs have been effective at setting and communicating strategy, but it’s clearly the domain of the chief executive.

Outside of the head or VP of product, most line product managers are not doing much strategy. A 2016 survey of 2,500 product managers and product marketers found that PMs spent only 28 percent of the their time on strategy, and 72 percent of their time on tactics or execution.

The same survey found that of seven major “superpowers” that a PM might possess (e.g. “Synthesis,” “Truth to Power,” or “Consensus-Builder”) the one that was the weakest, with over a quarter of respondents indicating “basic” or “no skills” in that area was Executive Debater, which they described as “Being a strong advocate for what is right in the market and challenging executive teams when necessary.”

At Etsy, I found that my job as a PM was primarily to make pre-determined ideas happen. While I sometimes was asked to “help come up with a strategy” for a product area, that was often a sign that leadership didn’t care about that particular area, and any ideas I came up with weren’t going to go anywhere.

As one progresses in their career in product, strategy will necessarily become a bigger part of their job, as it would for any major function: marketing, engineering, etc. And perhaps at firms where technology is not a core competency (finance, consumer goods, retail) product managers may hold more influence and drive the strategy more, I think that most tech-first firms (Facebook, Apple, Google, etc.) have a product strategy defined much higher up, and the role of the product manager is to work with the engineering and design teams to make that strategy happen.

People Management vs Stakeholder Management

The buck stops with the CEO, which means they have the ability to hire and fire. Typically this authority is focused on their own executive team, but if a CEO is really displeased with someone several levels below, that person’s tenure at the company may be at jeopardy.

Product managers are almost never the people managers of their team. Outside of hiring or firing PMs as a Group Product Manager or above, PMs have very little people authority.

If an engineer on their team is being difficult to work with, or a designer is unwilling to budge on a serious flaw in the product, they have to find a solution that doesn’t involve a carrot of a promotion/raise or the stick of firing.

Much of a PMs job is about convincing the people they work with. This is true from simple things like doing daily standups or writing tickets, tasks and user stories, to cutting a desired feature or pausing development to fix a particular bug.

All this is to say that product managers don’t manage people, but they do manage stakeholders. Austin Lin, a PM at Eeros, described these challenges as:

“Defending decisions that you don’t agree with both upwards and downwards, saying no 1000 different ways, being responsible for hard tradeoffs (picking what’s good enough over what’s perfect [and sometimes] squashing the dreams of engineers, designers, leadership teams)”

And it’s not just individual conflict. It’s about entire teams, and team-to-team conflicts. The number one challenge for product managers according to the Alpha 2016 survey was “internal politics.”

Beyond their immediate product team, PMs are often the point of contact for other product teams, other departments like Marketing or Sales, actual customers, and leadership. And these groups don’t always get along. So product managers have to make friends, present data, tell a compelling story, identify shared goals, cajole, beg, and sometimes twist arms to get things done.

This isn’t to say that CEOs don’t have to manage stakeholders, they do too: big clients and partners, board members, shareholders and analysts. But CEOs have certain authorities that PMs don’t, and it changes the nature of the job by quite a bit.

Resource Allocation vs Resourcefulness

As part of setting strategy, CEOs have the ability to allocate money, people, equipment, and other resources towards certain objectives.

When Chad Dickerson, then CEO of Etsy, wanted to make search a bigger priority, the company acquired Blackbird, a company specializing in machine learning, image recognition and analytics.

Casper, the mattress company, has spent enormous sums of money on display, outdoor, and subway advertising, a decision I would have to imagine was signed off at the CEO level.

Those are not decisions that a product manager can make.

That same product manager survey from Alpha that highlighted the challenges of internal politics also showed that product managers felt their #2 challenge was “lack of resources.”

The truth is, most things take longer than expected, and product teams are more often than not running behind schedule. A big part of the job of a PM is to get a project back on track or push out a launch date.

Sometimes that means letting people down. Peter Knox, a senior product manager at ShopKeep, shared this difficult aspect of being a PM:

[Having to tell] customers with genuine problems that you won’t be solving them anytime soon if at all

Cutting a project’s scope, finding creative ways to get more resources on a project, or finding a smarter way to solve the thorny problems are really the only three things a product manager has at his or her disposal.

Big Picture Vs Small Details

Fred Wilson, a partner at Union Square Ventures, shared an insight he learned early in his career from a 25-year veteran venture capitalist about the job of the CEO.

A CEO does only three things. Sets the overall vision and strategy of the company and communicates it to all stakeholders. Recruits, hires, and retains the very best talent for the company. Makes sure there is always enough cash in the bank.

I think we can agree that these are not easy tasks, and they are very high level. Life for a product manager is different, and requires a much greater focus on seemingly small details.

For instance, setting up a new team’s weekly team meetings. Every PM knows the pain of trying to set up a Monday team planning, daily stand ups, one-on-ones with your designer and tech lead, and than Friday demo meetings.

Trying to find time slots that work for everyone on the team, and a room that’s big enough and available at that time (ideally on a consistent basis) is the bane of every PMs existence. And yet, it’s just one of many critical tasks a product manager needs to take care of, from documenting decisions, to filing detailed bug reports, to doing manual QA on the product—because it makes our teams more efficient, moves our project forward, and isn’t likely to get done by anyone else.

0.1 Percent Money vs 10 Percent Money

Of course, one of the biggest reasons anyone would want to be CEO is because they tend to be paid well.

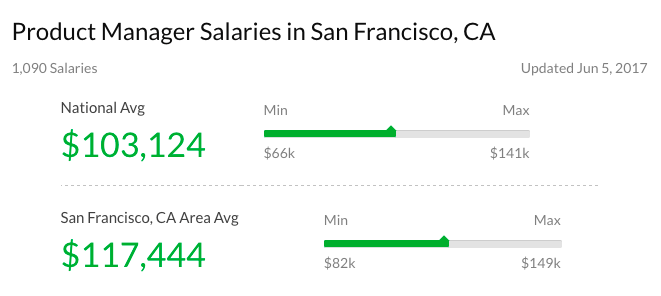

On the face of it, product manager salaries seem pretty strong. The national average, according to over 1,000 contributed salaries on Glassdoor, is $103k, which clocks in at the 89th percentile of income for individual earners in the United States (call it being in the 10 percent, though it’s likely that based on where many PMs are based, the percentile for that area is a bit lower)

However, this figure likely hides a wide range of titles. For instance, Google notoriously a wide range of salary bands inside of the title “Product Manager.”

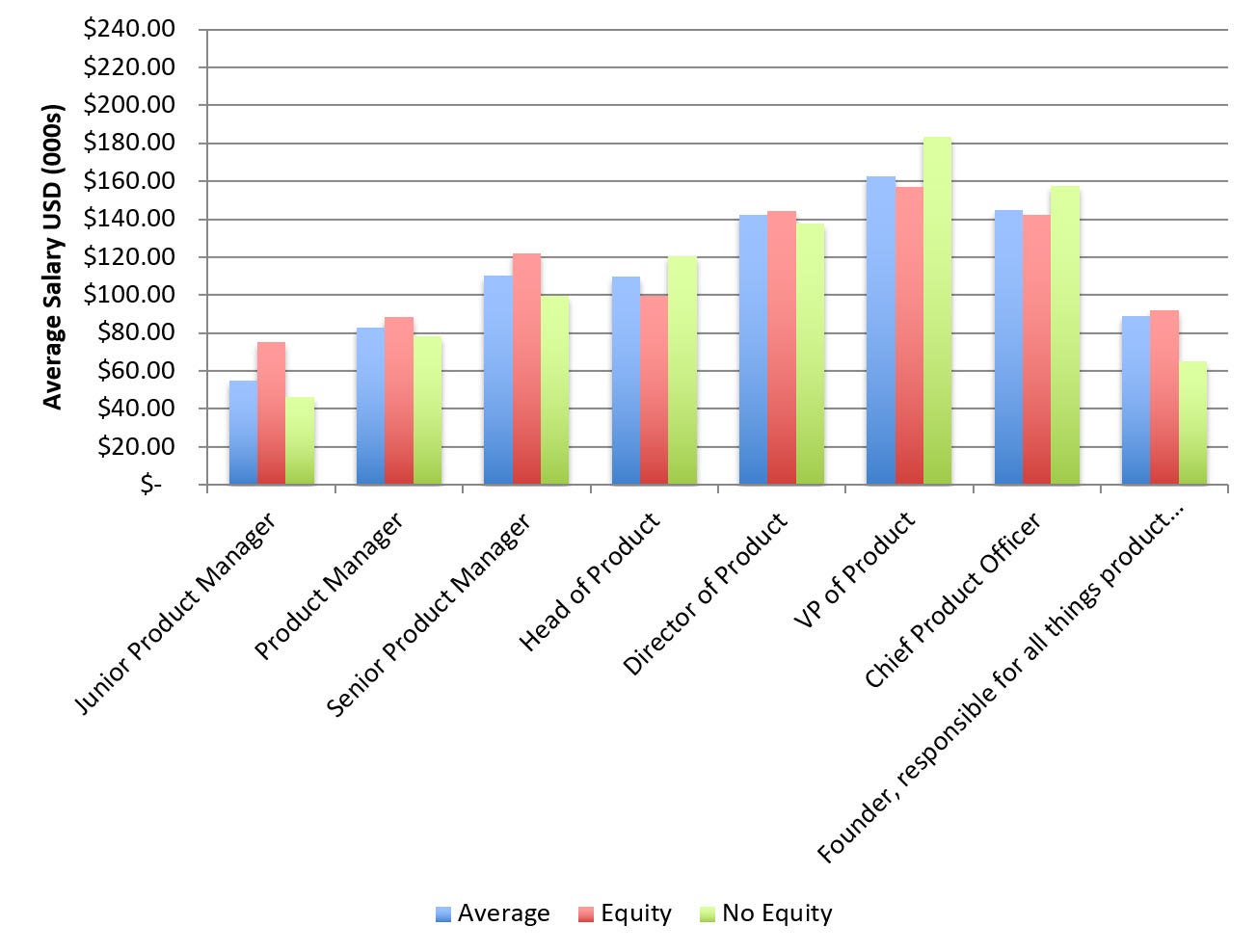

The 2016 Mind The Product’s survey breaks down PM salaries a bit more:

While this data is from a global survey, about three-quarters of the respondents were from the US or UK. Even adding a 15 percent fudge factor still puts a “Product Manager” title at $90k, with Senior Product Manager breaking the $100k mark and so on.

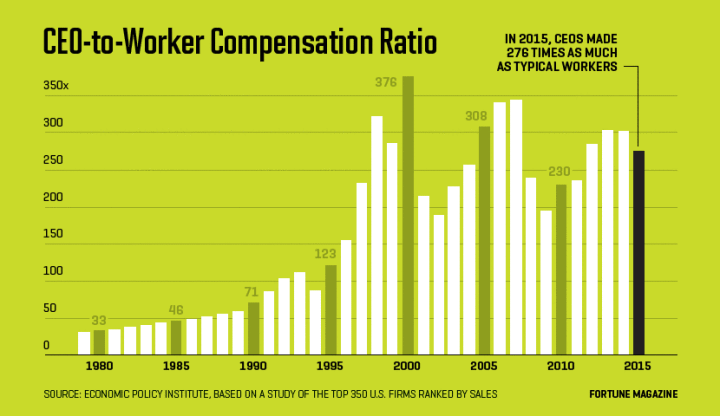

CEO compensation ranges much more widely than PM salaries given the size of the company one could be CEO of ranges dramatically. But here’s a chart of how CEO-to-worker compensation as changed over the years, now sitting at 276 times (!!) the average worker. At a mere $35k for that average worker, we’re talking about $9.6M for a CEO, which puts them in the 0.1 percent of earners in the US.

Perhaps that’s why AlphaHQ’s 2016 study of product managers which found their biggest wish for the next year was a higher salary. Does that mean PMs are just money hungry? Possibly.

But of course, it could just be that they’re comparing their “CEO of the Product” salary with the “actual CEO of a company” salary and feeling a little slighted.

The Emotional Tax

Despite everything I’ve said above, there is one thing that PMs and CEOs have in common. Being a CEO is tough. Tim Cook says that running Apple “is sort of a lonely job” and many CEOs agree, and feel that that loneliness impairs their performance.

While being a product manager isn’t necessarily lonely, the fact that we are the only one on our team, and not always well-connected within the rest of the organization can mean that PMs may relate to CEOs in feeling isolated.

The mental and emotional toll the job takes is well-known and quickly came to mind when I spoke to some PMs I know about it:

“Product management is a difficult, burnout-inducing profession. We do it because we love the idea of it more than actually doing it. I’ve hit the point in every product job I’ve ever had where I tell myself, “this is the last product job I’ll ever have.” Still, I keep doing product work, hoping that the next job I have will be the one that fulfills my expectations.” — David Schlossberg, product director at CrowdTap

and

“It is emotionally exhausting” — Kate Zasada, product manager at Paribus

and

“Sometimes you won’t be able to sleep thinking about a launch, but there’s little you can do yourself to ensure success”—Tami Reiss, product lead at JustWorks

I was only mildly surprised to learn that product manager was rated one of the unhappiest jobs in America in 2012. Having been a founder, marketer, consultant, and product manager, I feel like being a PM might have a lower day-to-day enjoyment but better long-term satisfaction (but only if you get to the point where you’re shipping regularly and have a team you respect).

For me, product management is exciting and stressful for the same reason: there’s unpredictability, there’s opportunity to create something new (which also means it may be unproven), and you’re usually operating with less data than you’d like, and everything is always a little bit broken.

Additional References

At the end of the day, software is still eating our world. From finance to manufacturing to transportation to healthcare, some of our largest industries are still at the early stages of their digital transformation. And with that transformation comes the need for product managers.

Building, maintaining, and evolving digital products requires a unique set of skills, an understanding of customers, technology, user experience, and the nuances of a particular organization and it’s political climate. It is a challenging role but one that can also be incredibly meaningful as well.

To learn more about this field, follow some of the links below.

source: medium.com