Author: Gregory Perry

So Uber partners with HackerOne to offer a public bug bounty program, advertising a $500 minimum guaranteed payout if a security vulnerability is found within an Uber app or information asset. Fair enough, I’ve led numerous penetration tests over the years in addition to delivering advanced pentest training for corporate clients.

I spent a few days getting some resources lined up for the analysis piece, and built a fairly comprehensive map of Uber’s various endpoints using subdomain enumeration and application fingerprinting. I also start kicking the tires of Uber’s Android app, which is locked down pretty tight per the Uber Bug Bounty Treasure Map with certificate-pinned HTTPS requests. After a few hours of wrangling with the Android SDK, I get the most recent Uber .apk running in an ARM emulator as they apparently don’t publish any x86 Android apps. Slooooooow progress to say the least.

I manage to bypass some of the certificate pinning security in the Uber .apk, sufficient to start mapping out some of the Uber mobile endpoints. There is reference in that traffic to a Microsoft Phone API, so I head over to the Microsoft Store and start testing the Uber Surface/Windows Phone app.

It doesn’t implement any type of certificate pinning, which is a violation of Uber’s own publicly-stated Treasure Map; so there’s the first guaranteed $500 payout per their bug bounty.

Uber uses OAuth2 tokens for all of their mobile app authentication workflow, which has a lot of security benefits over old school cookie-based authentication methods. I put together a Python-based client that can talk to Uber’s backends to start harvesting OAuth2 tokens, but what’s weird is the OAuth2 token doesn’t ever change, and I can’t find anything in the Uber developer documentation that deals with token expiration; literally the same token I was issued when I first created my Uber account for testing is the same token I keep getting, no matter how many times I log in and out of my account using the Surface app. Surely Uber is expiring these tokens at least once every few days?

I put that issue on the back burner and start probing the Uber promo endpoint, which has two pretty glaring vulnerabilities in that it doesn’t implement any type of rate limiting for promo code POSTs nor does it require any multifactor authentication. Or in other words, I can fire up an HTTP load testing suite to issue thousands of promo code POSTs to this endpoint, to enumerate OAuth2 tokens; in a few minutes I am able to enumerate over a million OAuth2 tokens, without any type of IP blacklisting or rate limiting taking place.

Back to the token expiration issue. This Surface app doesn’t actually communicate with the Uber backend whenever it processes a logout event, and I am able to access all Uber rider endpoints using my OAuth2 token even after the Surface app logs off. Huh?

So Uber is processing mobile app logouts locally, without any type of token expiration or invalidation taking place. That’s a big one, and now I understand why there is no mention made to OAuth2 token expiration in any of the Uber developer documentation: because once a user creates an account with Uber, the OAuth2 token that’s issued never expires and their mobile applications only process logout events locally in the client itself. This is a big application security No No that maps to several public CVE and OWASP vulnerability definitions, so I submit the first round of these issues to HackerOne for payment.

Issue 1: The Uber Customer Promo Endpoint does not implement multi factor authentication resulting in the ability of an attacker to enumerate millions of OAuth2 rider and driver tokens.

Issue 2: The Uber Customer Promo Endpoint does not implement any type of rate limiting and/or IP address blacklisting resulting in the ability of an attacker to enumerate millions of OAuth2 rider and driver tokens.

Issue 3: The Uber Microsoft Surface/Phone app does not implement certificate pinning in addition to accepting self-signed certificates in violation of the “cn.uber.com is a RESTful API performed over certificate-pinned HTTPS requests” required by the Uber Bug Bounty Treasure Map.

Issue 4: Uber mobile apps are only processing logout events locally, resulting in OAuth2 tokens never being expired and with the ability to access driver and rider information after a user has logged out of their Uber mobile app.

So these tickets get assigned to Rob Fletcher with Uber’s security team.

Issue 1: Uber knows about this problem, we are going to fix it in the future. No payout.

Issue 2: Uber knows about this problem, we are going to fix it in the future. No payout.

Issue 3: Uber knows about this problem, we are going to fix it in the future. No payout.

Issue 4: Uber does not currently have the ability to expire issued tokens. We are going to address this issue with our next generation authentication framework. No payout.

At this point I’ve spent over a week of my time on this bug bounty that has a clearly stated $500 minimum payout policy; not one of these issues have been publicly documented as out-of-scope on Uber’s Bug Bounty Treasure Map and/or the HackerOne Uber Bug Bounty disclosure page; and, with the certificate pinning vulnerability directly contradicting the requirements of Uber’s Bug Bounty Treasure Map itself…?

So I file a mediation request with HackerOne. It gets assigned to Kevin Rosenbaum. His response:

I am sorry you are having a negative experience with this issue, but we have contacted the Uber App Sec team and they have confirmed with us that these are not security issues that are in scope on their program. I understand that this can be a disappointment but I can assure you that they looked at this report and gave it the proper attention it deserved. I hope you can continue to work on our site and I wish you the best of luck.

OK. Now I am determined to demonstrate a critical severity vulnerability that Uber can’t get around. It’s obviously open mic night in their infosec department, and I bet I can hammer them with something that they can’t dismiss as vaguely out of scope.

Another day of digging around and I can reflect query parameters from the https://m.uber.com mobile endpoint. Their Content Security Policy includes a whitelist for *.cloudfront.net. I can enable Cloudfront in my Amazon Web Services console and host whatever arbitrary JavaScript code I want there, to be executed by https://m.uber.com. These are two separate issues considered critical severity findings under Content Security Policy 3, in addition to the ability to reflect arbitrary whatever through their mobile endpoint.

I submit the report to Uber:

The udi-id request parameter at the https://m.uber.com/0-dfffb25d2cf6ceeb0a27.js mobile endpoint is copied into a javascript string encapsulated in double quotation marks, resulting in SSL-protected payloads being reflected unmodified in the application’s response. The script-src whitelist at the endpoint includes a wildcard *.cloudfront.net host, which could be used by any attacker with an Amazon Web Services account to provision an arbitrary cloudfront.net host to serve trusted files from. The endpoint also has a missing base-uri, which allows the injection of base tags. They can be used to set the base URL for all relative (script) URLs to an attacker controlled domain. In addition to the reflected XSS issue, both the script-src and base-uri issues are considered high severity findings under Content Security Policy 3.

I’m also able to bypass the Uber OneLogin SSO portal, resulting in source code disclosure from their internal uChat employee messaging system. It’s not as serious as the XSS/CSP issues, but I throw that in a second report for good measure.

Rob Fletcher gets assigned the ticket:

We’ll take a look into this one more time, but so far this is not a security bug that is in scope — you’ve failed to demonstrate Javascript execution in a modern browser and the other behavior you allude to with “generating some arbitrary text using single quotes” sounds like simple content injection, which is out of scope for our program.

Please refrain from making theoretical arguments for why something has security impact and instead familiarize yourself with our scope page and demonstrate actual security impact that is in scope per our guidelines.

Ok. So I’ve demonstrated reflected XSS through their mobile endpoint, but their WAF is apparently filtering double quotes to prevent arbitrary JavaScript execution, and Uber is attempting to constrain the definition of XSS to only JavaScript execution even though the XSS definition has been expanded over the years to several other code execution frameworks well beyond just JavaScript. And, I’ve been able to trigger JavaScript execution with this particular attack vector in older Webkit browser engines, but Chrome’s XSS_Auditor is jumping in to block the XSS due to partial quote escaping by the Uber WAF and Uber is using this to not pay the bounty.

Bug bounties are exactly that: a way of openly researching and then submitting reports on the discovered application and/or infrastructure bug, supported with adequate evidence to prove the report abstract. This isn’t, or at least should not be, some digital munitions service where I have to provide a full-on exploit to prove that an application or service is vulnerable to attack, because if I have to go to that effort then why not just legitimately sell the exploit on any one of a number of commercial exploit brokerage auction services?

Well whatever, I am already invested in this so I build another payload, this time evading their WAF and Chrome’s XSS_Auditor, by injecting an HTML form that says “ENTER YOUR UBER USERNAME AND PASSWORD” which gets perfectly rendered from https://m.uber.com:

Here is a login form. Not properly formatted, because I am not a web developer or professional phisher.

So now it’s a completely verified critical security vulnerability, with working POC that will harvest usernames and passwords from an Uber mobile endpoint, and SSL-protected with Uber’s signed certificate. The Uber development team gets involved, and additionally verifies that yes, they can execute arbitrary JavaScript code from any *.cloudfront.net host, so these are three distinct critical severity security issues: reflected XSS, HTML content injection, and a CSP that allows execution of arbitrary JavaScript from any *.cloudfront.net host.

So Uber pulls the https://m.uber.com endpoint, and starts redirecting the various offending applications to their OneLogin SSO portal.

Followed by locking and then closing without payment all of my submitted security reports, so that they can’t be viewed or publicly disclosed.

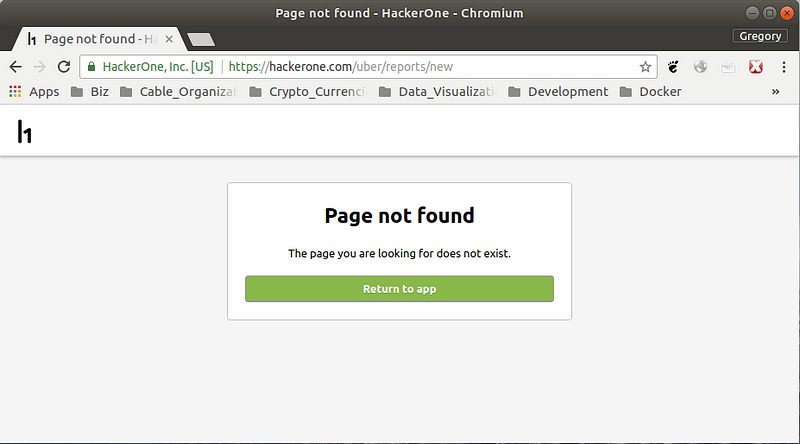

And now the HackerOne / Uber Bug Bounty report submission button:

TL;DR:

- Uber maintains GPS coordinate tracking data for tens of millions of people in the U.S. and abroad, so the security of their information assets is almost a matter of public interest.

- All of the recent bad press about the corporate culture at Uber is really real.

- Uber is not serious about their security efforts, and their HackerOne Bug Bounty is completely bogus.

- If you invest any time and effort into HackerOne Bug Bounties, HackerOne does not honor their minimum bug bounty guarantee, and will not go to bat for you if you have a dispute with one of their well-placed vendors such as Uber.

source: medium.com