Author: Greger Ottosson

If you’re into business strategy or product management, even if in a different industry, urban mobility is a market you should follow in the next 5 years. This article will give you a perspective on what’s happening and explain the dynamic behind the headlines and announcements coming at us almost daily.

Here’s what you should know:

- The first wave of ride sharing was enabled by a superior User Experience, a digital-only strategy, and bypassing of regulations

- The next wave will require vertical integration and capital investments for which Uber and similar ride sharing companies are not well-positioned

- Car sharing platforms, rental car companies and vehicle manufacturers will play a large role in the new urban mobility

The Changing State of Ride Sharing

In the last 10 years, ride sharing from companies such as Uber and Lyft came from virtually nowhere and grabbed a decent chunk of the urban and suburban mobility market. While established means of transportation (public transportation, cars, etc) evolved incrementally, ride sharing disrupted the taxi market and grew to address adjacent use cases.

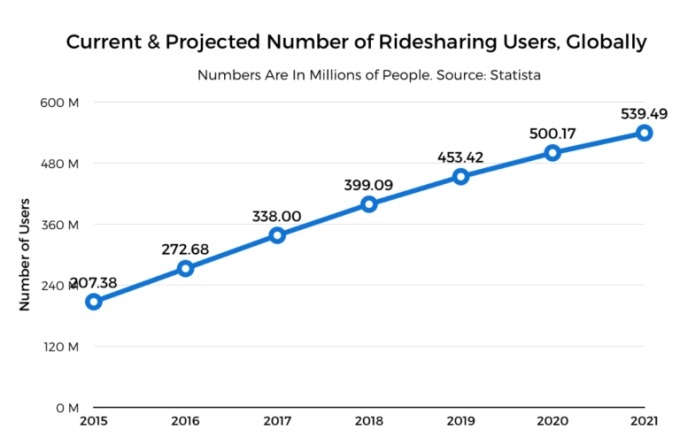

Ride sharing is projected to continue to grow linearly, reaching half a billion users in a few years:

So what happened? What enabled a new service to capture such a big portion of the taxi market in a relatively short period of time?

Uber and similar services grew fast based on an almost exclusively “digital” strategy:

- Leveraging personally owned cars, thereby avoiding capital investment in fleets

- Contracting drivers, thereby avoiding employment responsibilities

- Bypassing regulations, thus avoiding costs of taxi medallions, professional driver licenses, airport fees, etc

On top of this new business model, they delivered a vastly superior User Experience (UX), driven mainly by an easy-to-use and engaging Mobile User Interface (UI). Because the taxi industry had been protected and stale for so many years, the huge differential in UX drove rapid adoption of ride sharing through word-of-mouth.

Over the next ten years, further change is to be expected:

- Electric vehicles will become mainstream

- Cities will look to further reduce congestion

- Driverless cars will gradually enter the market

Will Uber, Lyft et al continue their rapid growth and emerge as winners?

To make a well-founded prediction one needs to look at what actually drives and shapes urban transportation.

The “Urban Mobility” Market

As always when looking at a market, there are two sides to consider: the user problems / use cases on one hand, and the solutions / products offered on the other.

Here’s an overview of the use cases and solutions in urban mobility. Self-owned vehicles are not shown, as they service virtually all use cases.

Ride sharing and car sharing are approaching the market from different starting points and are addressing different use cases. Neither has yet made significant inroads in the recurring use cases of medium complexity. Thus the path for growth is different for each.

The growth path for Ride Sharing

Ride sharing — being essentially just Taxi 2.0 — has mainly addressed the use cases of adhoc and infrequent nature, taking a bite out of the taxi market and expanding it somewhat through increased convenience and lower cost. Uber has not, however, become a staple for the average urban commuter with access to public transport, nor is it routinely used by parents lugging kids, gear and groceries between activities.

To effectively address these additional use cases, ride sharing needs to further lower costs to beat public transportation on recurring trips, and find solutions where goods and gear can be hauled in multi-stop trips. Without those additions, ride sharing will essentially remain Taxi 2.0.

However, the digital-only focus of Uber et al to date means that there are several core capabilities these firms have not developed. They don’t own cars and thus have no experience in fleet management like car rental- and transportation companies. They don’t have a strong track record in working with municipalities and public transport companies, so if you’re hailing a ride with Uber, you won’t be speeding along in the Taxi and Bus lanes, nor will you be picked up in special areas at the train station or airport where taxis are waiting. Those are luxuries that comes with conforming with regulations and paying the fees, as it were.

The growth path for Car Sharing

While ride sharing captured most of the attention in the last few years, car sharing companies were quietly evolving in the background, launching services in a growing number if cities across the world. Offering short-term car rentals, charging by the hour or by the mile, they offer a hassle-free way of accessing a car when you need one.

Initial services from early-movers such as ZipCar and Car2Go were typically station-based. You had to pick up and return the car from a specific location, similar to traditional car rentals. In the last few years, these services have shifted shifting towards “free floating” fleets, where you can pick up and drop off the vehicle at any public parking spot. Vehicle access has also been streamlined, often allowing you to open and access the car with a touch on your smartphone. These and other improvements have significantly lowered the friction of getting access to a car when you need it, and is enabling car sharing to grow further into the recurring type of use cases.

There are currently three types of players in the car sharing market.

1. Multi-city operators with Proprietary Platforms

Car manufacturers and car rental companies are now owning the largest operators:

- Car2Go (now owned by Daimler)

- ZipCar (now owned by Avis)

- ReachNow and DriveNow (owned by BWM in partnership with Sixt)

- Hertz 24/7 (owned by, you guessed it, Hertz)

- Maven (owned by GM, based on acquired Sidecar)

Similar investments or partnerships have also been made by Ford, Toyota, Enterprise, etc. In general, these companies both develop the digital platform as well as operate car sharing in select cities.

Car rental companies are experts in fleet management, while car manufacturers are not, which is why the latter have either acquired an existing car sharing startup or are partnering with a car rental company.

2. Local and Regional operators with 3rd-party Platforms

Besides the larger players listed above, there are dozens, maybe hundreds of car sharing operators with a smaller footprint. Sometimes operating in just a single city or within a country, these operators partner with platform providers instead of developing the software and hardware themselves. While they do need to make capital investments in acquiring cars, the UX and back-end comes from the platform provider.

3. Car Sharing Platform Providers

Several startups provide the platform for operating car sharing, without being operators themselves. Main players in this role include Vulog and RideCell,both with double-digit operators using their platforms. Typically, the platforms include all the components required to become an operator, save the cars themselves: the hardware required to outfit the vehicles with digital access and geo location, the Mobile UX for drivers, and analytics to support operations with fleet repositioning, vehicle maintenance, and more.

Why is there this distinction between platforms and operators? A look at the value chain — from physical cars to digital UX — will shed some light on this.

Value Chain for Ride/Car Sharing

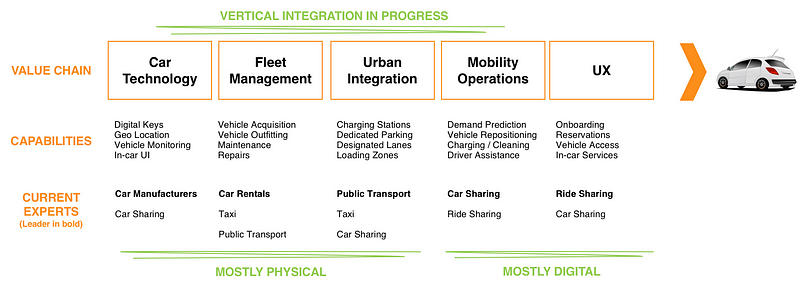

While Uber et al took the easy route with a purely digital platform, car sharing requires a different level of capital investment and vertical integration. Here’s the value chain, illustrating them both.

While ride sharing took a bite of the taxi market (adhoc, simple trips), car sharing is addressing more complex use cases (access to the same vehicle during multi-stop trips with kids and goods, for example). Delivering on these more complex use cases requires so-called backwards integration in this value chain.

For example, the car needs to be outfitted with digital keys, so drivers can open with their smartphone (integration between Car Technology and UX). Vehicles needs to be monitored for service needs and geo-located remotely (integration between Fleet Management and Mobility Operations). Parking- and charging stations needs to be acquired and managed (coordination between Urban Integration and Mobility Operations).

It’s tempting to imagine that this value chain could be modularized, i.e. that clear interfaces and standard will emerge for the hardware in cars, digital keys, in-car services and so forth. However, it will likely take a number of years until mobility platforms have been standardized while still able to handle city-specific regulations, traffic patterns and demand. Until then, backwards integration will be required to deliver the winning UX.

Summary and Predictions

Ride sharing operators like Uber, Lyft and Didi currently rely on drivers maintaining, re-fueling and monitoring their vehicles. As driverless vehicles emerge to form fleets, and electric cars demand charging infrastructure, there’s a lot of learning and investments required for current ride sharing operators that the car sharing operators are already managing. This include car technology, fleet management and urban integration.

Car sharing companies — often run jointly by car rental companies, car manufacturers and mobility platform providers— are in many ways better positioned to cover the whole value chain of activities required to take urban mobility to the next level.

Ride sharing disrupted a stale taxi industry on the easy use cases. The next wave in urban mobility will bring tougher competition.

source: medium.com