By Harsimran Julka

There are seldom some stories that have a profound impact on people or their tumultuous past. This story — From fleeing Vietnam in a refugee boat to becoming Uber’s CTO: the journey of Thuan Pham — on Tech in Asia ended up this month uniting the refugee boat’s captain and his passenger — about 38 years after they left the war ravaged shores of Vietnam on April 17, 1979.

The boat’s captain reached out in the comments box on Tech in Asia after reading this story.

The Uber CTO credits the captain for saving his life on the tempestuous ocean.

Both had tears while recounting the journey that nearly killed them and their families.

It also left a passenger dead, who had to be buried at sea. Thuan, who is now driving Uber’s technology worldwide, was about 11 years old, and the captain was all of 29 years back then.

Both recount what happened during those turbulent nights on the refugee boat which was rejected by two countries and towed back to the seas.

This story also left a deep impact on me.

David NienDuy Nguyen, former captain of MT-2377 and a Vietnam war veteran:

“I was MT-2377 boat captain, navigator, and representative at that time. My son, who was a four-year-old back then, emailed me the link to this story onTech in Asia which evokes all my memories as if it were yesterday. So, let me provide you with more details.

The MT-2377 left Cua Tieu, My Tho on April 17, 1979 with two other boats which sank right after they left Vung Tau. MT2377 was overloaded because the Cong An [Vietnamese Communist Police] dumped a lot more people on that boat as they had received additional bribe.

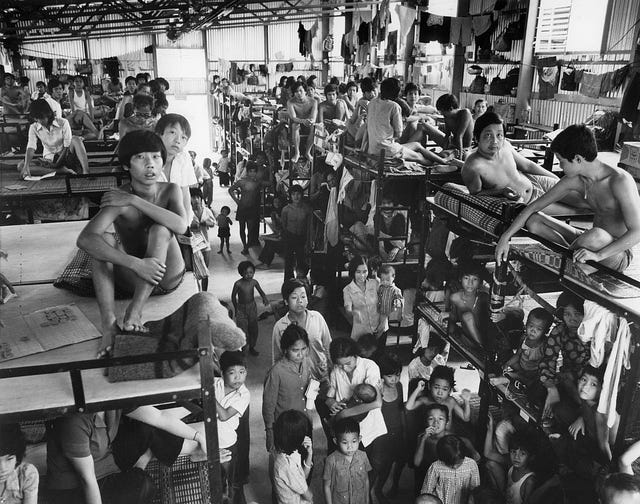

A refugee boat from Vietnam post the fall of Saigon. Photo credit: WUTC.org.

At that time, I thought that MT2377 was going to sink.

To my surprise at that time of the year — ‘thang ba ba gia di bien’ literally means in lunar March an old woman can sail to sea too — our boat was caught in a strong storm.

At that time, I thought that MT2377 was going to sink. One of the owners of the boat — Mr. Xap Dzach [Mr. Eleven] told me ‘we’d better go back’ … but looking down, the water color looked like café au lait, brownish, which indicated the boat was close to the river estuary. It was raining hard and almost impossible to see the estuary and the boat could get grounded and capsized.

So I decided not to come back but instead sailed the boat straight to high sea on bearing 120. It was a right decision. The boat is supposed to bobble up and down in water, but not get grounded. After about one hour, the water turned to dark blue which means we were in deep water and safer.

Vietnamese refugees rest as crewmen aboard the guided missile cruiser USS FOX (CG-33) give them something to drink. June 1, 1982. Photo credit: Wikipedia.

Young men on the boat nailed close all little windows on starboard and port for ventilation. Unfortunately, during storm times, these openings got sea water inside the boat. [Thuan was at one of those ventilations.]

Luckily, our engine and water were functioning perfectly — many thanks and appreciation to Tai Cai and his son and his big family — who with his experience had chosen a reliable good Yanmar boat engine that ran faultlessly until the end of the trip! Had the engine and water pump stopped working at that time, we would all have been drowned. — dead boatpeoplefeeding the sharks!

We left Cua Tieu, My Tho with 472 persons. When sailing past Con Son [Pulau Condor] a 70-year-old man died of exhaustion.

I asked that family not to cry out loud, pay respect to the old man the last time, then wrapped the old man with a cloth and silently slipped his body into the ocean. By doing so, it would avoid panicking other people on board and infection.

British Red Cross run Hong Kong Kai Tak North refugee camp, which housed 15,500 Vietnamese. Photo credit: British Red Cross.

Our boat, when it sailed past Con Son, was stopped again by a Cong An patrol boat which again demanded money. Someone then had to climb over a perilous rope connecting our boat and the communist patrol boat to pay ransom before we could go again.

The next day, our boat was stopped by a Thai pirate boat. Fortunately, these pirates were humane in a way that they asked for dollars or gold. They did not commit any rape or killing. They even told the other Thai pirate boats — which were circling around us — to go away because they already took all our valuables.”

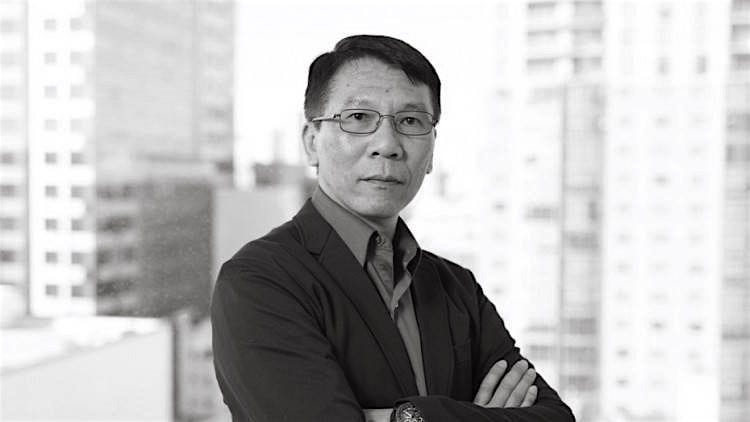

Thuan Pham, chief technology officer at Uber:

“I do remember the name of the captain — Nien Nguyen. The family he brought with him on this journey was his wife, young son, and two teenage brothers. The captain was in his thirties back then.

It was a stormy ocean one night and the boat was going up and down. We thought that was it. Later, I realized how skilled the captain was — he took the boat right into the waves. Sailing parallel to the high waves may have capsized the boat.

The storm happened exactly as the captain has described. I was lying in vomit next to engine room on the port side of the boat and remembered seeing a wall of water a few storeys high all around us. Somehow the captain was able not to get us all drowned. The captain describes the storm in greater detail (above), as he was the one getting us through that storm.

When you face death like that, it doesn’t matter that this event happened 37 years ago, you just don’t forget it.

When you face death like that, it doesn’t matter that this event happened 37 years ago, you just don’t forget it.

After the tumultuous journey we crashed our boat onto the Malaysian soil one evening in May 1979. We were all taken to a refugee camp inside Malaysia.

After our boat landed on Malaysian shores, I vomited a lot of sea water and was lying on the shore due to sea sickness. I could meet my mother only after sometime.

We were rejected as refugees from Malaysia, but we didn’t have a choice to take “another boat”.

We were forced/booted out of Malaysia on our own boat. And here’s how it happened.

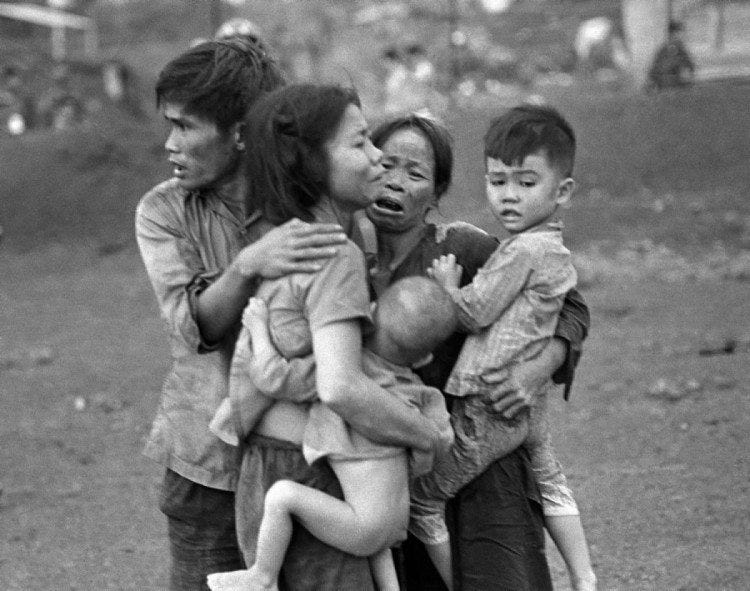

South Vietnamese survivors of a mortar attack comfort each other. Vietnam War, 1965. Photo credit: Photo credit: AP/Horst Faas (1933–2012).

A week later, the entire group of people on MT-2377 were packed back onto our boat and ejected from Malaysia. A Malaysian navy ship towed our boat out to the open sea for several days, and we ended up in Singapore.

Singapore did not let us go on shore, so after being stuck on the Singapore harbor for several days [with food and water supplied by Singapore authorities], we were towed back out to the open sea again.

We finally ended up in the Anambas islands in Indonesia, in the town of Letung.

Then we were resettled into the Kuku refugee camp, where we remained for 10 months until we were able to emigrate to the USA.

I was the boy who lived right next to the captain’s family in the same barrack on Kuku Island! When he taught English [since he was fluent and was the boat representative] to the students on the island, I would often sit right there and listen to his lessons.”

This month (July 2017), both sent me a picture of themselves they clicked in Los Angeles in Captain Nguyen’s Home.

“We still remember our time on Kuku island like it was just yesterday,” Uber CTO Thuan Pham.

The article was published in medium.com