By Harsimran Julka

This is Diwali season in India – the festival of lights, gifts, and joy, when migrants from all over come back home. And I am in an Uber cab in Delhi. The person I am pooling with is wearing sunglasses. It’s about nine in the night.

He is talking to someone on his mobile phone, consoling her, saying that he will be there for her. After his call gets over, I suddenly hear strange voices in the cab. He is hearing WhatsApp and Facebook messages, sticking his Android phone to his cheek, close to his ear.

I glance at his phone’s lit screen. Foodpanda, Gmail, Flipkart, WhatsApp, Facebook, Ola, Google Drive, and of course Uber. I notice that he did not see me looking.

I hear all those motivational messages – the usual forwards – on his WhatsApp, being read rapidly by an American-accented male voice. “It’s a wonder you can decode the language when it is in a foreign accent. That too when it is playing super fast,” I remark, breaking the ice between us.

“It has become a habit now,” he says. I address him as Hemant — the name displaying on the UberPool app.

“I am Raman. Hemant is just an alias to earn another free ride with Uber. I created a fake account,” he tells me.

Then I learn that Raman a.k.a Hemant is a graduate of St Stephen’s College in Delhi, who got picked up by the Uber cab from Corporation Bank, where he works, near Connaught Place. Raman is visually challenged.

The security guard from the bank helped him board the Uber, the driver told me, later.

My favorite app

“Which is your favourite app?,” I ask.

“Uber is one of the most accessible,” he tells me. His Android speech reader can easily read the buttons on the Uber app.

Image uses photo from Pexels.

“What about Ola?,” I ask.

“There is a challenge with Ola and some other apps. They make ‘stars’ to rate drivers and don’t write text at the bottom – I can’t read. We cannot rate the driver,” he says.

In most apps, a new ride or booking cannot take place if you haven’t rated your previous driver or service provider.

“App makers should remember us as well. I have written multiple times to Ola asking for their developers to make the app accessible to all. There has been no reply,” he tells me.

The cab passes by Lutyens’ Delhi zone. This is where the most powerful of Delhi live – an area lined with bungalows. “Houses are getting lit up. There will be a Diwali mela here soon,“ I tell him. “We are crossing the Oberoi Hotel flyover,” I relay to him as we travel.

“Yes, the Diwali mela by the school children of Blind Relief Association. That’s where I am from. I studied there till class twelve,” Raman tells me. I could sense his heart fill with nostalgia.

We go back to talking about apps.

The problem of Captcha

“What about Facebook and WhatsApp?” I ask.

“On WhatsApp, I don’t know if a friend of mine has seen my message. WhatsApp displays a blue tick. But my Android speech reader cannot read symbols,” Raman tells me.

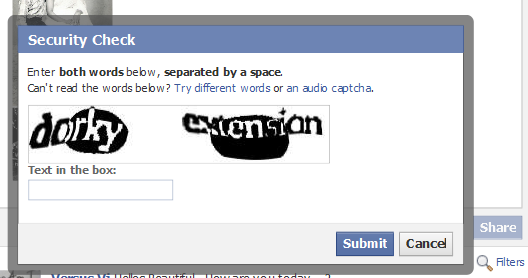

Another big challenge with many apps is the ‘captcha,’ which makes them unusable by millions around the world. India is home to about 15 million of the 39 million visually impaired people in the world.

Facebook asks users to read captcha and so does Google, when you forget your account details. But they forget that about 39 million people in the world can’t.

Photo credit: Fred Miller.

“If you make a captcha mandatory for logging into a Facebook or an internet banking account, we can’t use the app,” Raman tells me.

In India, HDFC Bank uses captcha. Indian Railways provides a customised app for the specially abled, to let them book train rides.

When apps become #NotOkay

Accessible apps write the sign ‘Ok’ on the buttons.

“Some apps just make an enter symbol instead of writing ‘OK’. I can’t use that,” he says. The cab passes by the Dargah of Hazrat Nizamuddin, a Sufi saint. Raman senses the mosque is nearby from the hum of the devout.

“Please go straight, he tells the driver.”

As we turn into Jangpura, there is a traffic jam, perhaps due to the weekend Diwali shoppers.

Photo credit: Ondasderuido.

“Do you buy online,” I ask.

“Yes, I do. My suggestion to ecommerce companies is to write ‘Buy’ on their buttons rather than just making a cart symbol. I use both Flipkart and Amazon,” Raman tells me.

As we pass by a Diwali bazaar, he can sense the bylanes. Sounds of a temple bell nearby, the smell of a dairy shop, and the bark of a familiar dog. “There is a park on your left,” he tells the driver.

“You’ve reached your destination,” Google navigation announces to the driver.

“Can you please hold my hand?,” he asks me.

I get out of the cab and hold his hand. He guides me.

We struggle through the crowded Diwali bazaar. The shopkeepers are selling gold-painted earthen lamps, red and yellow candles, and strings of artificial flowers in various hues. Chinese lanterns are a favorite, it seems. Blue, pink, and purple. Lanterns shaped as orange flowers hang from makeshift bamboo canes. Gods have found their place too in the bazaar. Idols of Ganesha and Lakshmi are stacked in rows.

Photo credit: Pixabay.

Strings of yellow LED bulbs light up the bazaar. Rockets, wheels, torches, sparklers, and fountains – fireworks of all varieties are in full display. Kids are seen arguing with parents at cracker shops. The shopkeepers gaze at us and then turn a blind eye. The hordes press against us. We get split twice. I go back to search for Raman and hold his hand again.

“There will be a motorcycle near a staircase at the end of the lane,” he remarks.

“Yes, I can see it,” I reply. “Should I escort you up?”

“No. I am fine. Thank you,” he says, grabbing a railing on the staircase.

- An earlier version of this article appeared on Medium.

The article was published in techniasia